Indemnity Ordinance, Fifth Amendment . . . and Collective Memory

Syed Badrul Ahsan:

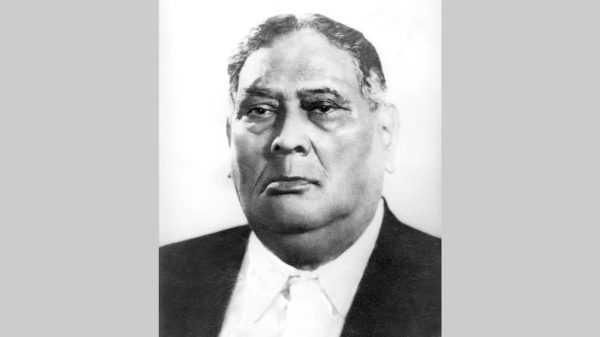

Forty five years ago this month, on 26 September 1975 to be precise, the usurper regime of Khondokar Moshtaq Ahmed promulgated the infamous Indemnity Ordinance that effectively blocked any prosecution of the assassins of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

It was a hard slap on the face of national history. And it turned into a huge blow when the military regime of General Ziaur Rahman had the ordinance injected into the Constitution as part of the Fifth Amendment by the Jatiya Sangsad, dominated by his newly formed Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), on 6 April 1979.

For those of us who remember, for those who may have forgotten, for the generations of Bengalis born post-August 1975, it is important today to revisit the darkness that was deepened by the Indemnity Ordinance. In this year when we as a people observe the centenary of the birth of the Father of the Nation and mourn his passing in dreadful circumstances forty five years ago, it is of critical importance that we do not forget the horrors we lived through for twenty one years until June 1996.

When the Indemnity Ordinance was promulgated by Moshtaq, not a single member of the cabinet — all of whom had been appointed to office by Bangabandhu — protested the move. Not one minister resigned, not one minister demonstrated any degree of courage and defiance when the ordinance was imposed on the country. Those whom the usurper regime was afraid of were in prison — Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad, M. Mansoor Ali and A.H.M. Quamruzzaman. One, Kamal Hossain, had refused to be part of the cabal and stayed away from the country.

Manoranjan Dhar could have voiced his protest at this violation of the concept of rule of law. General M.A.G. Osmany, as defence advisor to the commerce minister-turned-president, was influential enough to prevent Moshtaq from going ahead with indulging in the notoriety. He did not act. The three services chiefs — Ziaur Rahman, M.H. Khan, M.G. Tawab — were all beneficiaries of the violent coup of August and would not lift a finger against the ordinance. Khaled Musharraf and Shafaat Jamil, who were to become extremely active in early November of the year about restoring the chain of command in the army, were not unduly worried at this blatant attempt to exonerate Bangabandhu’s assassins and have them strut around on the nation’s creaky political stage.

The Indemnity Ordinance was a shame we as a people have not yet been able to live down. Men who had served in Bangabandhu’s government — Mohammadullah, Yusuf Ali, Korban Ali, et cetera — went on to demonstrate their loyalties to the military regimes of General Zia and General Ershad. Not one of them raised the issue of the ordinance in their extended careers. Opportunism was the order of the day.

The Indemnity Ordinance led to ramifications, of an ominous sort. It was an assault on history. It was a projection of immorality in its most sinister form. In the five years in which Zia presided over the fortunes of the state, many of the assassins were sent off abroad as diplomats for the country. An intriguing part of this sordid tale is that the countries to which these murderers went, in the raiment of diplomats, did not ask the regime why the assassins of Bangladesh’s founding father, rather than being brought to justice for their criminality, were being sent to their capitals as diplomats.

The Indemnity Ordinance was a deliberate bottling of the truth. On every celebration of Independence Day and Victory Day, no mention was made of the circumstances that had led Bangladesh’s people to a triumphant War of Liberation. Bangabandhu was airbrushed out of the narrative; the Mujibnagar government did not find space. Worse, the tale spun by those who held power in those twenty one years referred to the ‘occupation army’ of 1971. The younger generation thus had no way of knowing that the occupation army belonged to Pakistan, that it was a force that had led millions of Bengalis to their deaths. Pakistan was not mentioned.

There were other ramifications of the ordinance. In December 1975, with President A.S.M. Sayem in Bangabhaban but General Zia calling the shots, the Collaborators Act was repealed. History was stood on its head when ageing Bengalis who had sworn fealty to Pakistan even as their compatriots were being killed and raped in 1971 by the state they adored made a cheerful return to the political centre. None of these collaborators would ever express remorse for their perfidy during the war and yet, thanks to the long shadow of the Indemnity Ordinance, they would end up serving, in those intolerable twenty one years, as ministers and lawmakers in a land they did not want to be born.

The Indemnity Ordinance would spawn murders and intrigues for twenty one years. The killings of 3 and 7 November were perpetrated in absolute impunity. The hundreds of soldiers and airmen arbitrarily executed by the Zia regime, the eighteen abortive coups against the regime, the hanging of Col Taher in questionable circumstances, the murder of General Zia and General M.A. Manzoor, the execution of thirteen army officers in 1981 and the ouster of the elected government of President Abdus Sattar were all a fall-out of the Indemnity Ordinance. If Bangabandhu’s assassins could go free, everything else would be a free-for-all.

In the Ershad dictatorship, the Indemnity Ordinance facilitated the path for the formation of a political outfit by the 15 August assassins. It opened the door for one of the assassins to seek the nation’s presidency and for another to occupy a seat in the Jatiya Sangsad.

The Indemnity Ordinance and with it the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution have been a blot on the collective conscience of this nation. Those who were instrumental behind these dangerously regressive moves have never been prosecuted, even posthumously. An entire state machinery was employed to undermine the state, play truant with it and set the clock back by more than two decades.

The Indemnity Ordinance carried a grim message: that it was all right for rule of law to be cast to the winds. It brutalized the state and dehumanized citizens. Those responsible, dead as well as alive, for infecting national history with this deadly virus need to be brought to account.

Closure can happen only when the dark stains of the Indemnity Ordinance have been fully wiped off the canvas of Bangladesh’s history.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a writer and columnist

Leave a Reply