The world won’t escape the aftermath

SELDOM in European history has an invading power so exaggerated its own strength, and underestimated that of its enemy to the degree that Russia did when it attacked Ukraine on 24 February. Ten months after president Vladimir Putin ordered the Russian army to conquer Ukraine, the tragic absurdity of his giant blunder remains staggering.

Russia has never recovered politically or militarily from that initial miscalculation about the likely success of an invasion — and it is difficult to see how it can do so in future.

Putin believed that his ‘special military operation’ would face negligible resistance so he could easily install a puppet regime in Kyiv as the Ukrainian government and army fell apart. When this piece of wishful thinking was swiftly exposed as a fantasy, Putin turned out to have no Plan B, as Russian forces faced stiff Ukrainian resistance and failed to capture the capital and other big cities. Soon, a 60km-long Russian military convoy stalled for weeks on the road north-west of the capital became a symbol of Russian failure.

Putin was seeking to roll back the expansion of NATO influence and revive Russia’s status as a super power. By invading Ukraine, he achieved the precise opposite, as NATO aid poured into the country and Russia’s reputation for military competence was left in shreds. Its army was exposed as a badly-led, poorly equipped, ill-disciplined force that proved unable to capture a city like Kharkiv a few kilometres from the Russian frontier, and it only took Mariupol in the south-west after a two month siege.

In April, Russian troops withdrew from north of Kyiv as Russian strategy unravelled. By then, it had become clear that Russia did not have enough soldiers on the battlefield if it was going to resist a well-armed Ukrainian army supported by NATO. Obvious though this deficiency was to everybody, the Kremlin pretended to the Russian public that it was fighting a limited war and there was no need for a mass mobilisation, something Ukraine had carried out at the start of hostilities.

It was only after a humiliating Russian defeat by a Ukrainian counter-offensive in September in the Khar2kiv area, where Russia turned out have had few regular troops, that Putin ordered the conscription of a further 300,000 soldiers.

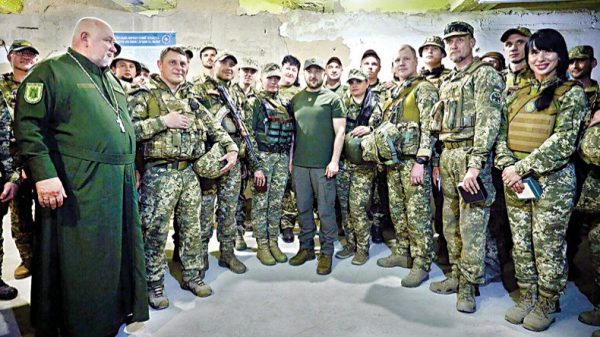

As a warlord, he has emerged as one of the greatest bumblers, portraying himself as a master strategist despite being repeatedly caught by surprise. Aside from an inner circle of cronies, few have influence on him, and his frequent reshuffling of front-line generals has failed to make up for basic weaknesses in numbers, training, equipment and organisation. Mass mobilisation when it came was shambolic, with conscripts rushed to the frontline as soon as they learned how to fire a gun. Given that the Ukrainian front line is 2,500km long, according to Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, both sides are vulnerable to surprise attacks.

Many Russians may wonder: what happened to their air force? The Pentagon and NATO had promoted Russian airpower as a mighty instrument of war, which could only be countered by vast expenditure on new aircraft, such as the F-35 at $80 million a plane. In the event, Russian aircraft were never able to control Ukrainian skies and are reportedly incapable of evacuating their own wounded to hospitals in the rear.

The list of Russian military inadequacies is a long one, but it is important to understand that it has not yet lost the war. Its reverses are humiliating, such as the retreat from the city of Kherson to avoid troops being cut off on the wrong side of the Dnieper River, but the withdrawal made military sense.

The melodrama of the ground war in Ukraine attracts most of the television coverage and gives a triumphalist and deceptive impression of undiluted Ukrainian success. But I remember how, in the Afghan war in 2001, the United States and its Afghan allies were convinced that they had conclusively defeated the Taliban. A couple of years later, Washington was declaring ‘mission accomplished’ in Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and then found its soldiers fighting for their lives in a war that had barely begun.

I do not believe that Putin can reverse his gross strategic errors in launching the invasion in the first place. Russia’s enemies are too numerous, too well-armed and too united for it to defeat them. But that does not mean that Moscow has no military options. Russia may lose in the sense of failing to achieve its war aims, but what will a post-war Ukraine look like?

Just as jubilant Ukrainians were celebrating the blowing up of the Kerch bridge and the recapture of Kherson city, the Russians started to systematically destroy Ukrainian electricity generating and transmission systems, using precision-guided missiles and drones. This was denounced as a war crime, but 30 years ago the United States knocked out Iraq’s power stations, sub-stations and transmission systems by similar means in the Gulf War of 1991. At that time, the United States largely monopolised these precision-guided means of attack, but no longer. In 2019, Iran briefly crippled Saudi oil production by the same means and now Russia is doing the same in Ukraine.

More and more Ukrainians have been plunged into darkness since October, without light, heat, fresh water or sewage disposal. NATO powers are rushing in air defence missiles and emergency generators which will mitigate the impact of the destruction of the electric grid. But day to day life is going to be very tough for tens of millions of Ukrainians whose factories, farms and offices can no longer function. This does not mean that the Ukrainians will run up the white flag, but they will pay a heavy personal price for an endless war.

The effect of the war in its broadest sense is being felt far beyond the frontiers of Ukraine, damaging the world economy as a whole, but with countries differently affected. The absence of cheap Russian oil and gas, and reliance on imported liquefied natural gas, hurts Europe more than the United States. American leadership of a more powerful NATO has been strengthened. Russia will probably emerge from this conflict as a shrunken power but nothing in war is predictable, particularly in one like this that has so many players with contrary interests.

Nobody knows how long the conflict will go on. Even if the fighting does die down for a few months this winter, Ukraine and Russia both believe that they can make gains on the battlefield. There is more talk of diplomacy and negotiations, but it is difficult to see what a lasting peace would look like. Biden said in early December that he is willing to talk to Putin, but there is no reason why he should let the Russian leader off the hook.

For now, Putin appears to have no rivals inside or outside the Kremlin, but can he survive in the very long term his unforced error in starting a war that never had any upside for Russia? On the other hand, Saddam Hussein lasted 13 years after his equally disastrous invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

The Ukraine war is like an ulcer that is poisoning the rest of the Europe, but so far nobody knows how to cut it out or stop it bleeding.

CounterPunch.org, January 2. Patrick Cockburn is the author of War in the Age of Trump (Verso).

Leave a Reply