Anti-Semitism Is Part of Pakistan’s DNA

Amb Wali-ur Rahman:

When Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan whose government is talking to the Islamists of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik-e-Pakistan (TLP), desperately trying to avoid a diplomatic embarrassment with Europe, said on April 19 that TLP and his government had “the same objective but our methods are different,” he was stating the obvious.

He was also betraying something the Western world knows, but does not officially admit it with regard to an on-again-off-again military ally, that anti-Semitism runs deep in Pakistan’s DNA.

Two strong indicators emerge from Khan’s current tussle with the TLP, triggered by the latter’s demand for expulsion of the French envoy to pay for the Charlie Hebdo cartoons of last September that Muslims consider insulting to their faith.

They are: One, the TLP has emerged as a “never-before” threat to the Pakistani state, to quote a warning from Najam Sethi in his editorial in the Friday Times. This qualification is serious considering Pakistan’s record of flirting with Islamist extremism, both in domestic arena and for exporting it to its neighbourhood.

Two, a more serious one: the Khan is widely perceived as playing the Pakistan Army’s proxy. Its failure to tackle the dangerous rise of religion-driven militancy is a direct reflection on the army and its hold on the country’s governance.

And this extends to the fact that the army itself has a long record of nurturing Islamist militant groups, using them when and as required and discarding them the purpose is served. This was admitted from his Dubai exile by former president, General Pervez Musharraf, who said in a media interview how various groups and their leaders, nurtured especially since the 1980s (the anti-Russian conflict in Afghanistan), were ‘heroes’.

As for the TLP, to recall one of its high-profile campaigns last year, it had wanted the government to hang Asia Bibi, a Christian woman accused of blasphemy incarcerated for long years, even after the country’s Supreme Court had acquitted her. The Khan Government, fearing a certain backlash from the world community, quietly flew her out to Canada where she remains under threat, like many Pakistani civil society leaders who have fled the country to escape the twin wrath of the state and the militants.

Why we say anti-Semitism is part of Pakistan’s DNA? That is because the state is ideology-driven, an ideology that excludes others. Students are taught in schools that Hindus are Kafirs (a pejorative) and Christians and Jews are enemies of Islam, liable to be killed for no other reason. There are few Jews left, if any, while the remaining religious minorities form only four percent of its 200 million population.

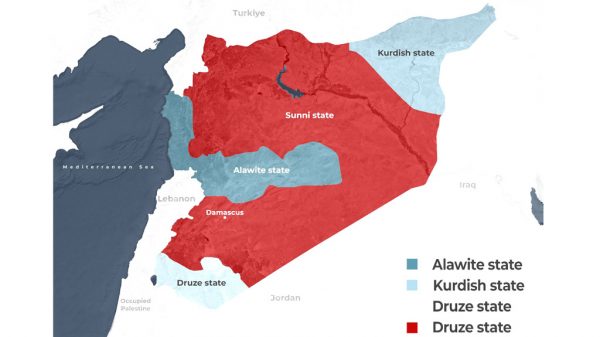

A year after Pakistan was carved out of British-ruled India, in 1948, partition of Palestine and establishment of a Jewish state by the Zionists caused feelings of resentment and humiliation among Muslims. Right from the day of creation of Israel, Pakistan not only refused to accept Israel but adopted a hostile attitude towards the state of Israel.

More recently, Pakistan-based and trained terrorists who attacked Mumbai in 2008 attacked Chabad House, the Jewish cultural centre in the city killing many of its occupants. Messages exchanged by the youths and their handlers back in Pakistan showed that this place was a special target.

Tensions between Jews and Muslims were exacerbated due to 9/11 that also uncovered deep mistrust between them. Many Muslims alleged that Zionist and Israel Secret Service could be behind the attack on World Trade Centre. They made wide use of the Protocol of the Elders of Zion and accused the “Zionist controlled media” for launching massive propaganda attack against Muslims and scapegoating Muslims and Islam. It was also said that “The Elders” changed the scheduled visit of P.M. of Israel to US a day before 9/11 attacks. They directed 4000 Jews not to report on September 11, so no single Jew employee was reported killed or missing, according to these conspiracy theorists.

The latest post gone viral on the social media is quoting a top Japanese scientist who claims that Coronavirus is not natural, but man-made and that it was triggered at a laboratory in Israel.

Anti-Semitism in Pakistan is rampant. At the beginning of 20th century, in the largest city of Pakistan, Karachi, about 2500 Jews engaged as tradesman, artisans and civil servants. By 1968, the number of Jews in Pakistan had decreased to 250; almost all of them were concentrated in Karachi, where there was only one synagogue, a welfare organisation and a recreational center. Most of them prefer to pass themselves off as “Parsees”, or Zoroastrians, due to intolerance for Jews in Pakistan (Shields, 2008).

Historically, Pakistan has maintained a hostile attitude towards Israel. Pakistani leaders have long placed themselves at the forefront of the “anti-Zionist” struggle and see it as their commitment to their Islamic credentials.

The atmosphere for minorities in Pakistan is usually portrayed as anything but peaceful. At the centre of the popular discourse on this topic lies an emphasis on everyday experiences of violence, discrimination and exclusion. Issues range from a lack of access to education, sanitation, transportation and health care, to occupational discrimination and more direct experiences of violence such as abductions and forced conversions, accusations of blasphemy, targeted killings, and frequent attacks on places of worship. This portrayal of religious minorities in Pakistan seems to suggest that little or no normal life is possible for them.

Since the introduction of the so-called ‘blasphemy laws’ between 1980 and 1986 during the dictatorship of President Zia-ul-Haq, academic discussions on minorities have mainly turned to two topics: the political implications of these laws, and the persecution of the country’s Christian community. Both aspects are often discussed as intricately tied together. With regard to the Christian minority, likewise, its status as a beleaguered, marginalised and persecuted community has been emphasised time and again.

Unsurprisingly, much of the current discourse on minorities seems to suggest that their lives are left untouched by broader historical, social and political developments, as if they are floating in a timeless and unbounded void. It implies that their situation is locked into a permanent and unchanging present with no hope for improvement, while the larger society around them is constantly evolving.

This lot of the minorities is and shall remain pathetic since the majority Muslims are themselves divided and violently at logger-heads as evident from the government-TLP tussle. It leads to an inescapable conclusion that the leadership in Pakistan, like many other Islamic countries, having created and nurtured the Frankenstein, succumbs to their street pressures.

Needless to say, Israel’s decision to open its mission in Islamabad is fraught with risks of inviting hostilities and targeting by Islamist radicals.

The writer is a former diplomat

Leave a Reply